Ambassador Event: Arizona’s Water Position

Published: 09/30/2021

Updated: 02/09/2023

Arizona’s water supply remains strong following Colorado River declaration

Decades of intentional planning and long-term solutions are why Arizona’s residential and municipal water users will not be affected by the first-ever shortage along the Colorado River.

The 18% reduction resulting from tier-one mandates equates to only 8% of the state’s total water use.

Arizona’s vast aquifers, a multi-faceted portfolio of water supplies and the most advanced program for managing groundwater in the country, coupled with the legal and physical infrastructure to maintain a 100-year assured water supply, positions Arizona differently than its neighboring states in the west.

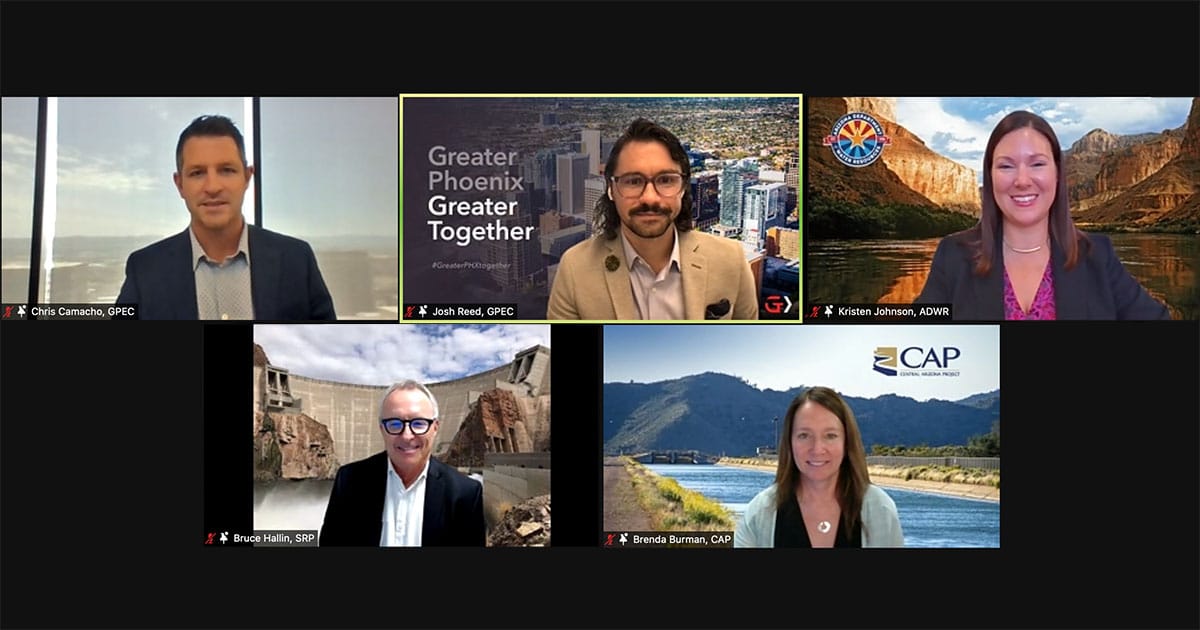

Local water experts joined our latest Ambassador Event to discuss Arizona’s water position and how the state is planning to ensure the availability of natural resources like water in the future.

Panelists included:

- Brenda Burman, Executive Strategy Advisor, Central Arizona Project

- Bruce Hallin, Director of Water Supply, Salt River Project

- Chris Camacho, President & CEO, Greater Phoenix Economic Council

- Kristen Johnson, Colorado River Section Manager, Arizona Department of Water Services

- Moderator: Josh Reed, Senior Director of Communications, Greater Phoenix Economic Council

Arizona water background

Despite the massive surge in population, water usage in Arizona has gone down over the decades; less water is used today than in 1957 and the state has five times more water stored than it uses.

Three major projects were instrumental in establishing the infrastructure to solidify the state’s current water supply. The Central Arizona Project, authorized in 1968, established more than 300 miles of canals that pipe water from the Hoover Dam and Lake Mead reservoirs south through Phoenix and Tucson. Today, about 80% of the population in the region receives water through CAP.

“The Colorado River water we receive comes through the Hoover Dam and Lake Mead,” Burman said. “Together, these two infrastructures and our other dams hold about four times the flow of the Colorado River.”

Twelve years after CAP was established, the 1980 Groundwater Management Act was signed. It created the legal and physical infrastructure to assure a 100-year water supply.

The Groundwater Management Act limited groundwater mining to preserve the source as a backup supply, mandated conservation requirements and required new growth to rely on renewable water supplies, as well as created the Arizona Department of Water Resources and the five Active Management Areas, which encompass about 80% of the state’s population.

“I can’t underscore enough the importance of that piece of legislation,” Johnson said. “It established a framework for the comprehensive management regulation of the withdrawal, transportation, use, conservation and conveyance of the rights to use groundwater.”

The Salt River Project contains a 13,000 square-mile watershed using reservoirs and the Salt and Verde Rivers to serve roughly 400 square miles of service territory, primarily in the metro area.

Through these plans, Greater Phoenix has several different sources. Thirty-six percent of Arizona water comes from the Colorado River, 41% is groundwater, 18% comes from in-state rivers and 5% is reclaimed water.

Almost three-quarters of it are used for agricultural purposes. Seventy-two percent goes to agriculture, 22% to municipal and 6% to industrial. The reduction along the Colorado River, which will account for 512,000 acre-feet next year, will not impact municipal or residential uses.

“All the infrastructure that you see in place, it isn’t for normal situations – it’s for drought. What system can you think of across the U.S. where you can have a 20-year dry period and just now be going into shortages?” Hallin said. “These systems are doing exactly what they were designed to do.”

Impact on business development

As the Greater Phoenix market evolves, industrial growth within advanced electronics and semiconductor sectors is at an all-time high. With this comes a heightened priority placed on water rights and access.

Because cities operate their water and land differently, the GPEC business development team works with companies evaluating the region to select parts of the area that are most ideal for both the success of the company and the growth of the region.

“From a land-use perspective, from an energy and load-growth perspective and a water capacity perspective, I’m seeing very diligent conversations occurring about the best use of land,” Camacho said.

When companies and the firms that represent them seek out GPEC and other economic developers in the region, it is important to remove the assumptions that Arizona is in the same position as the western states that are struggling to manage their water supplies.

“I’m very optimistic,” Camacho said. “Scarcity management, conservation and augmentation practices are still going to be vital as our community grows, but we’re in a very positive spot.”

Remaining proactive

SRP is looking for opportunities to expand storage space at its dams and reservoirs. For example, water in the flood control space at Roosevelt Dam must be released within 20 days, but the organization is speaking with engineers and the Bureau of Reclamation about extending that period to 120 days.

SRP also found a long-term project opportunity to add up to 300,000 acre-feet of additional storage capacity water to the Verde system and use it for those who have limited access to CAP or SRP water.

Desalination is a long-term goal. Studies are in effect for constructing plants potentially on the Sea of Cortez or near Mexicali in Baja California. Johnson estimated that these works remain a decade out from any sort of operation.

“In the very near-term, we also need to keep our eye on conservation and using our water wisely,” Johnson said.

Reforestation has particular importance in the future of Arizona’s water. The increase in wildfires has led to a rise in sedimentation, impacts on water quality and cost to treat the water supply.

“We’ve been working together with the forest service and the state of Arizona and others on essentially moving forward on a restoration program, the largest in U.S., to restore these [overgrown] forests to a more natural condition,” Hallin said.

While Arizona has been prepared for decades, the drought has had its impact. Water levels between reservoirs at Lake Powell and Mead have dropped drastically since 2000, when they were almost full, which led to guidelines created in 2007 and a drought contingency plan put into place in 2019.

Arizona is not running out of water, but the effects of droughts, sedimentation and climate change are forcing the state to remain proactive, just as it has been for the last 50 years.

“More action looks like it’s going to be needed,” Burman said. “We’re coming together again, with the states, with the federal government, tribes, NGOs, to look at what more can we put onto the table to make sure we have a stable water supply.”

More background: Fast Facts on Arizona’s Water Position

Meet our panelists:

- Brenda Burman, Executive Strategy Advisor, Central Arizona Project

- Bruce Hallin, Director of Water Supply, Salt River Project

- Chris Camacho, President & CEO, Greater Phoenix Economic Council

- Kristen Johnson, Colorado River Section Manager, Arizona Department of Water Services

- Moderator: Josh Reed, Senior Director of Communications, Greater Phoenix Economic Council